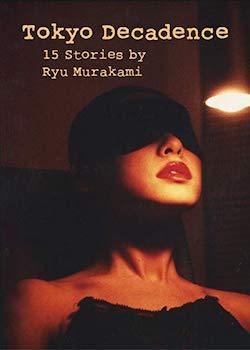

Tokyo Decadence: 15 Stories

By Murakami Ryū

Translated by Ralph McCarthy

Kurodahan Press (2016)

ISBN-10: 4902075784

Review by Chris Corker

There was a time when writing about sex was a taboo, authors treading the line with innuendo-laden prose about as adept at concealment as Adam and Eve’s fig leaves. Nowadays, everyone’s aunty has read Fifty Shades of Grey and, to their younger relations’ horror, finds it a bit dull. The boundaries have been well and truly pushed, for better or worse, and what we are left with is a society that is as desensitised to sex as it is to violence. In fact, the recent success of a certain book-come television series goes to show that a little titillation and dismemberment can be just what the sales doctor ordered.

Of course, it goes without saying that between the period of suggestive whispers and the current ‘it’s nothing I haven’t seen before’ generation, there was a transitional phase. Even when the envelope seems to be pushing itself, on closer scrutiny there are a group of disgruntled, disenfranchised individuals urging it forward with all their might, if only to see what might happen. We tend to call these individuals pioneers, and there is no doubt that Murakami Ryū was one such man. In a conservative 1970s Japanese society that didn’t always see much merit in deviating from the norm, it was inevitable that characters like Murakami and indeed director Miike Takeshi, who filmed Murakami’s novel Audition, would spring up like weeds through Japan’s finely-raked rock garden, bringing with them an extreme approach poised to challenge preconceptions and cause disharmony.

A rebellious youth, Murakami was placed under a three-month house arrest for barricading the roof of his high-school, before later dropping out of college to focus on his rock band and 8-millimeter film making. Many of his books are heavily-autobiographical, dealing with drug-use, a rejection of the establishment and the cultural abrasions caused by US military bases. His first novel, Almost Transparent Blue, an account of a vicious cycle of sex, drugs and rock, was first published in 1972, when Murakami was still at university. It went on to the win the Akutagawa Award, Japan’s most prestigious literary prize. It is telling that while critics accused the author of decadence and condemned his work, others hailed the book as a stylistic revelation. Murakami had been moulded by the times, and was supported by a strong counter-culture current. Being a man of the times, however, can be a double-edged sword. The question that formed in my mind as I began reading Tokyo Decadence’s collection of short stories was whether Murakami Ryū was still relevant in an age for which the original revolution is a distant speck on the horizon.

After reading the first stories of this collection, connected by topics of prostitution and unusual sexual proclivities, my initial conclusion was that their intention was simply to shock. From a trucker that enjoys self-emasculation and dressing up as a woman to the lurid details of a prostitute’s clients, Murakami seems at pains to lay everything out, warts and all. In fact, given his cross-oeuvre penchant especially for sex and the sex trade, some of the stories can feel a little familiar. There’s something to be said for linking stories through a theme, but when synergy becomes repetition, it’s clearly a detractor.

Throughout the book there are moments when it feels as if the author has gone out of his way to be extreme, only to then lose a little bit of the gritty realism that is his domain. (‘In eighteen months Kimiko had aborted three pregnancies, slashed her wrists twice, had sex with countless black GIs, and got herself arrested twice and rushed to hospital with heart failure once.’). You feel that the desire to shock is always at the forefront of the author’s mind. There is sexual mutilation reminiscent of American Psycho; one character tries to recall a quip about a dead baby, while another opines that ‘people who suffer all the time shouldn’t be allowed to live.’ But the question here must be whether or not a sustained current of the extreme doesn’t lessen the impact. Often the most shocking elements of story-telling are nestled between soft, fluffy pillows of serenity or cool understatement.

Comparisons with his namesake, Murakami Haruki, are unavoidable given their joint prominence in Japanese literature. Beyond this, there are also further similarities of topic. Both authors deal frankly with sex, write extensively about jazz and seem equally obsessed with baseball. Even their favoured backdrops have a habit of overlapping, most conversations taking place in either run-down or swanky bars in Shinjuku, and other central Tokyo locations. And while Murakami Haruki’s forte is, to borrow the title of Jay Rubin’s book, ‘the music of words’, where the humdrum is elevated to something beautiful, Murakami Ryū is more of a pragmatist, preferring to slap you around the face with the soiled condom of truth than romanticise. Whether admirably truthful or tactless, that’s just the way he writes. Although, it is hard not to cringe at lines like: ‘…penetrated my frazzled brain and body like a vibrator.’ And cringe I did at other lines suitable for a man who at times thinks he is far more hip and daring than he now appears.

The second half is stronger. Yes, it deals with sex but also with human relationships beyond the bedroom. Written later in Murakami’s career, these stories feature the autobiographical elements of working in the film industry and the author’s passion for Cuban music. Three stories in particular, each featuring the recurring character of Meiko Akagawa, stand out from the rest with their tragically flawed characters searching fruitlessly for their dreams. Also evident here is the unique ennui born of living in one of the most technologically advanced and comfortable countries in the world.

‘In this country it’s taboo even to think about looking for something more in life […] something significant is missing, and that’s something Japan never had.’

This extract is from the strongest piece, ‘Historia de un Amor’, a story about the fluxing vividness of life, and one that considers whether being first-world necessarily means being first-rate. Murakami’s descriptions of Cuban music are also most prevalent here, and his love for the genre radiates from the page.

So my question from earlier still stands: Is Murakami still relevant for readers in our desensitised age? Is an author, whose modus operandi is to shock, but no longer has the power to do so, still serving a purpose? Like a politician I will answer these with a few questions of my own. Are you a fan of what is often termed ‘Asia Extreme’? Are you keen to see the – sometimes exaggerated – darker side of Japanese life, hidden beneath Hokusai postcards and pictures of monkeys in hot springs? Are you willing to forego some pretty shameless attempts to shock in order to discover the finer points of a clearly talented author? If you answered yes to these questions, you will find plenty to like in this collection, and perhaps we can allow the revolutionary to reign for a little longer, before he too is dethroned by another.